The Memorial’s Story

Imagine the Zlín of 1930, 1931…

A dynamic garden city in which “Nothing Is Impossible”. Baťa’s employees, over 30,000 in number, are busily distributing over 30 million pairs of shoes worldwide each year. But then comes 12 July 1932, when Tomáš Baťa – who is also serving at this time as the mayor of Zlín – dies in an air accident. On exactly the same day a year later, a brand new building overlooking the city opens up to the public as a tribute to the city’s founder – and a place to commemorate him forever.

The Tomáš Baťa Memorial Is Born

The project’s architect, Baťa employee František Lýdie Gahura, chooses an unconventional approach: instead of using a complicated exhibition to describe the company head, he uses the structure itself, inscribing into it Baťa’s fundamental personality traits: broad-mindedness, clarity, flight, optimism and austerity. The exhibition’s main artefact is a faithful rendition of a Junkers F13 – the plane that ended Baťa’s life journey.

It is an Architectural Gem…

Gahura created his masterpiece from a mere three materials (glass, iron and concrete), without using a single brick. It takes the classical “Zlín Standard” (a reinforced concrete skeleton frame made from 6.15 × 6.15 m modules) used for nearly all of the Baťa concern’s buildings (factories, dormitories and schools) and manoeuvres it into an entirely new form. Stained glass, atypical lighting (light from soft upward-facing lamps reflected off the ceiling) as well as hidden symbolism underscore the uniqueness of the resulting architectural work.

…But Its Appearance and Utilisation Saw Changes

After World War 2, the Communist party takes over in Czechoslovakia. Highlighting Baťa’s heritage is no longer politically desirable. Zlín is renamed by government decree to Gottwaldov, the Baťa company is nationalised and then renamed to “Svit”, and the Tomáš Baťa Memorial is turned into the “House of Art”. In this period, the architect Eduard Staša adapted the building to serve the needs of this regional art gallery and the local philharmonic. These institutions would be housed in the former Memorial for nearly the next sixty years. And these waters remain unstirred until the Velvet Revolution.

A Return to Democracy – and to the Memorial’s Intended Purpose

After 1989, Zlín gradually cast off the inheritance of Communism. The philharmonic and the art gallery were moved to better-suited spaces, and the building on the slope of “Gahura Avenue” began waiting for its new use. Following a society-wide discussion inspired by an idea from the British theorist Kenneth Frampton, an architecture teacher at Columbia University in New York, the decision was made. The building underwent a two-year renovation led by the architect Petr Všetečka and was reintroduced to the public in 2018 in its authentic appearance from the 1930s under the name “The Tomáš Baťa Memorial”. Since 2019, this space has been accessible all year round in the form of guided tours.

“Any visit to Zlín should end right here.”

Adam Gebrian

Promoter and architectural theorist

Historic milestones

Even though the Tomáš Baťa Memorial is relatively young for a historic building, its history so far has been highly dynamic. Including a transformation into an art museum and back. Its story is made up of a series of both ordinary and extraordinary moments. Here are a few of the most interesting.

Central characters

Tomáš Baťa

Born: Zlín, 3 April 1876

Died: Otrokovice, 12 July 1932

Shoemaker, industrialist and mayor. And aviation promoter. At a time in which the southeast of today’s Czech Republic is still covered by nothing more than roads on which, as locals would say, “our cows would break their legs”, Baťa develops a bold thesis: “The air is our sea.” And thus at a very early date – in 1924 – he buys his first aircraft, and air transport becomes for him the most effective way to connect Zlín with the world. One of the best-known journeys in this respect is Bat’a’s business trip to India (1931–1932), for which he sets off from the company airport in Otrokovice, to head off towards Calcutta, Batavia and back, making a series of stops along the way. The over 30,000 kilometres that Baťa travels in an aeroplane flown “by eye”, navigated only by the terrain below, give proof of his courage and trust in his pilots.

Both of these, however, soon come to cause his death. On 12 July 1932, disregarding all recommendations against it and despite unfavourable weather, he orders a departure for Möhlin, Switzerland. His pilot Jindřich Brouček loses his bearings in the fog and angles the craft towards the ground at full speed. One year later, Baťa’s plane “ascends” for the very last time inside the Memorial, as a permanent memento of the factory owner’s life philosophy.

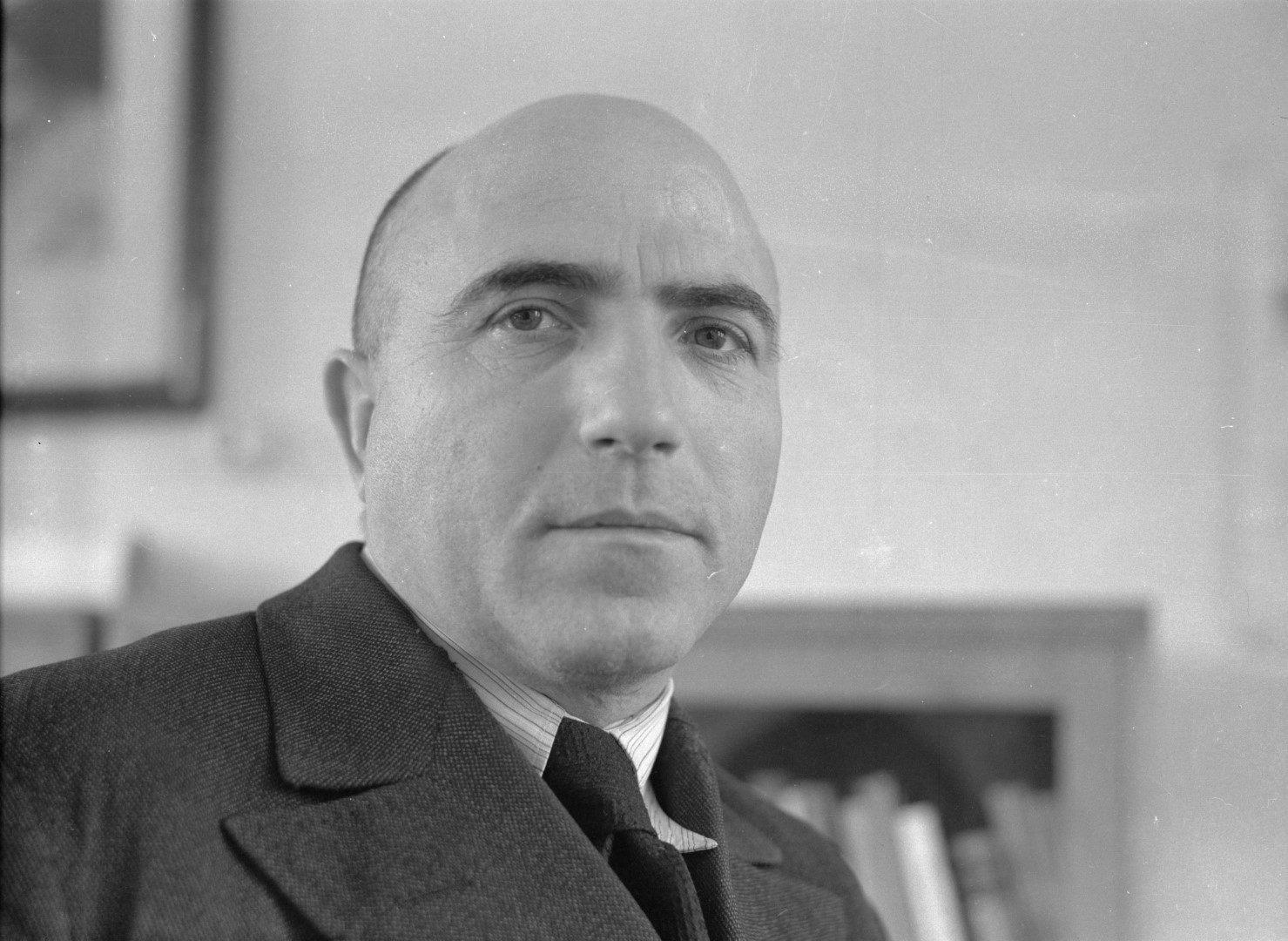

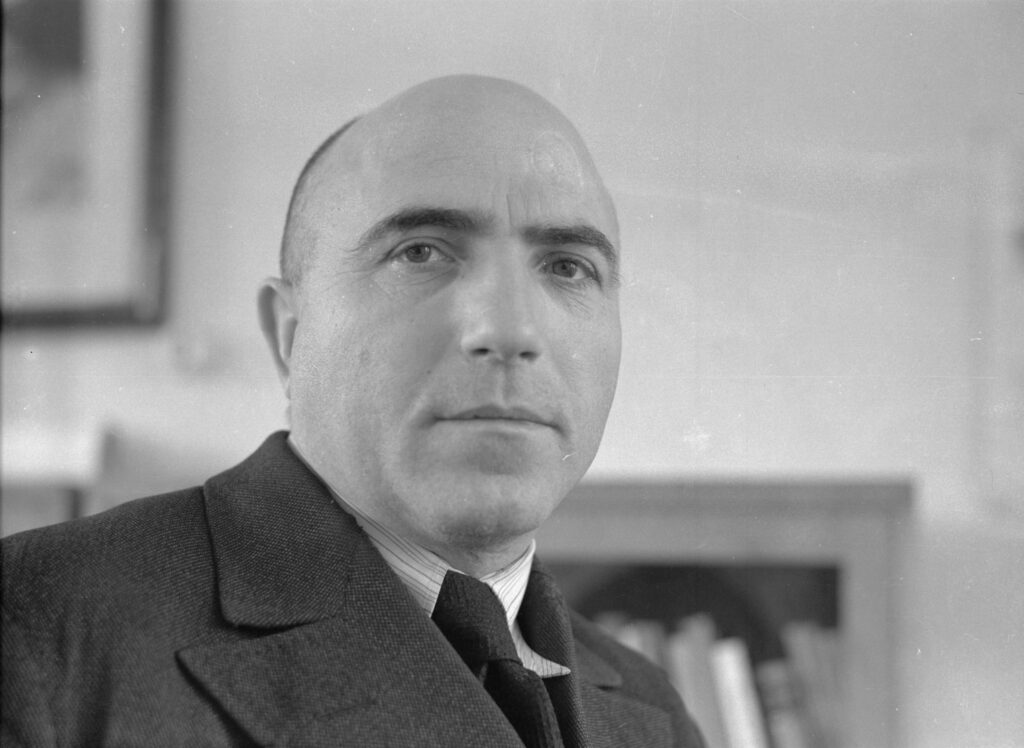

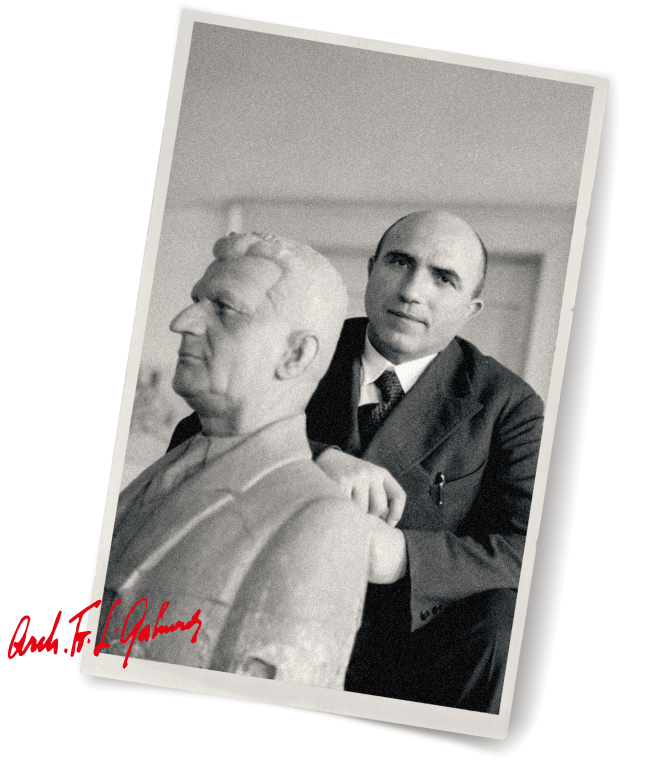

František Lýdie Gahura

Born: Zlín, 10 October 1891

Died: Brno, 15 September 1958

From sculpture to architecture, from architecture to urbanism… František Lýdie Gahura’s professional career may seem murky at first sight. But his achievements speak for themselves. Under the patronage of Tomáš Baťa, Gahura – a disciple of Josip Plecznik and Jan Kotěra – blossoms into an outstanding figure of architecture in Zlín and beyond. In 1924–1933 he works for Baťa’s shoemaking concern as a full-time employee, and he remains in the city until 1945. In cooperation with Tomáš Baťa (and later his brother Jan Antonín Baťa), he designs the town’s zoning plan and develops the concept of garden districts. Gahura’s architectural designs are used in the construction of Zlín’s hospital, schools, department store, cinema and boarding schools, and a long list of other buildings.

It is thus unsurprising that Gahura is also the man behind modifications to Baťa’s villa, the plan for the Forest Cemetery – the place of Baťa’s eternal rest – and above the Memorial. In this radical building, Gahura fully expresses the experience he has acquired in the above-mentioned fields. He has created a building that is simultaneously a sculpture. A sculpture whose design elevates it into a symbol. And in the end, it is Gahura’s ability to “overflow” that gives the Memorial that which we have come to call its genius loci today.